Ol Pejeta - Kenya’s Rhino Capital

One of the strongholds for both black and white rhino, and home to the last two northern white rhinos in the world, Ol Pejeta’s conservation work is critical to the species.

This blog isn’t really meant to be a wildlife portfolio, but I can’t deny that the wilderness of Africa is one of my favourite travel destinations. That’s partly for the landscapes (Namibia stands out), the unexpected (check out the dinosaur footprints in Zimbabwe), or the conservation efforts (see my trip to Amboseli for IFAW), but of course also for the animals you can find here. This is another blog focused on the latter. I promise though there will be future entries again covering other parts of the world, with cityscapes, landscapes, and possibly a few humans as well…

For now, we are going back to Kenya, not far from where I had the joy to photograph Giza, the famous black leopard. Specifically, a conservancy called Ol Pejeta, at the foot of Mount Kenya. This region is rich in wildlife, but stands out for one species more than all others: Rhinoceros.

I’ve wanted to come here for a few years, having followed the faith of a specific type of rhino for a while…but one thing at a time.

I stayed at the aptly named Porini Rhino Camp, a simple tented camp in the quiet north-eastern side of the conservancy. It’s a beautiful small camp in a very calm location, with wildlife just metres away from your tent. It was also completely empty - the season had just started (this was in mid-May) and we were the first guests after they re-opened. Could not ask for more!

The Water Hole

The camp also features a small hide directly at the local waterhole - always a great option to get some eye level close ups of animals coming to drink - giraffe, impala, warthogs were among the visitors as we arrived.

This brave warthog came pretty close to the hide but was rightfully skittish - the smallest sound and movement made it scuttle away quickly.

Centre of the World

The conservancy lies in the north of Kenya at the equator, which runs through its borders, marked by a small sign post. I’ve had the chance to cross the equator on foot a few times before, but it’s still a cool little quirk to move from one half of our planet to the other.

Ol Pejeta is also home to a large variety of birds. I’m still learning to appreciate our flying companions more, but even with my limited knowledge seeing one of these colorful bee-eaters in action is always a joy…

… as was this incredible and rather unusual (so I was told) sight of probably more than a hundred pelicans gathering in a small pond just off the dirt-road leading through the part of the conservancy.

Rhino Capital

Admittedly it wasn’t the birds why I came here. It was for Rhinos. Ol Pejeta is one of their strongholds in Africa, with around 50 southern white rhinos such as these ones, more than 150 critically endangered black rhinos (the much more shy variant) and the last two northern white rhinos on the planet (yes - the last individuals of the species anywhere, whether in the wild or captivity).

We had at least a dozen rhino encounters over the 5 days here, with several groups spread around the conservancy. Its borders are designed in such a way that rhinos cannot move beyond its boundaries with specific type of fences and deterrents that only allow all other animals to pass and migrate. This is for their own protection: Ol Pejeta employs highly trained rhino protection squads, partners with international veterinary experts and gathers data on all of the individuals to support their conservation across Africa.

The Northern White Rhino

The pinnacle of the conservancy’s conservation work sits behind this fence: the enclosure of its two Northern White Rhinos, the last of their kind.

I’ve been following their faith for a few years and had been looking forward to learn and see more of them in person for a while - it was an exciting moment to stand in front of these gates.

One of their caretakers (I think his name was Noah) tells the story of Fatu and Najin (her daughter): In 2009 four of the world's last remaining seven northern white rhinos at the time arrived at Ol Pejeta.

Najin, Fatu, Sudan and Suni were a family that had been living in a zoo in the Czech Republic, where previous breeding attempts had been unsuccessful.

The hope was they would reproduce here in their native habitat, but this didn't materialize. By 2018, Sudan, the last male of the species, died, leaving only the two females we have now.

Several attempts were made to mate them with a southern white rhino, which now lives with them in the enclosure, but this also proved futile.

The Last of their Kind

As we entered the huge fenced area, the three rhino in the area weren’t all that far: Najin and Fatu to the left, with their southern white rhino companion on the right side. The northern variant is a bit smaller, less hairy, has a straighter back, flatter skull, and shorter horns. The group is protected 24/7: in total, the conservancy has almost 250 people in security, with over 40 armed rangers, and the protection of the rhinos costs $1.5m per year - mostly financed from donations.

Owing to their history in a zoo, these rhinos are quite accustomed to humans, and may even let you feed them - a moment where you can feel their strength even in the most docile of movements.

The last wild members of the species are said to have been spotted in the mid 2000s in the DRC - with no sightings in the last 15 years they are considered extinct in the wild. With no other captive population either, these two are probably the rarest mammals on Earth.

Both females are no longer be able to produce offspring on their own. The last hope of the species now lies in the development of in vitro fertilisation techniques and stem cell technology. The rangers told us excitedly that just a few days before my visit, researchers had attempted an in vitro process using a southern white rhino surrogacy female. This has unfortunately not been successful - read more here.

One last touch

We got to spend almost an hour with these (mostly) gentle giants. Even a few months later it gives me goosebumps to think back the feeling to encounter these creatures so closely and be able to touch their skin and horn - the last remnants of an entire species of animal that may not exist anymore in a few years from now. A sober reminder of the fragile environment we live in these days, given that rhinoceros have been around for 50-60 million years.

Baraka - the blind black rhino

Another close encounter you can have here is with a rhino that was saved from certain death in the wild: Baraka, meaning “blessing".

He lost sight on one eye due to a battle with another male, and a bit later his other eye was affected by an infection, rendering him completely blind.

Luckily for him, rhinos generally have poor eyesight, and instead mostly rely on touch and hearing to navigate the world around them. That made it possible for Baraka to enjoy a relatively peaceful life in a huge enclosure.

Although he got used to humans around him and is generally calm, his massive horn makes Baraka an imposing creature. It’s not surprising that when a local school class approached, not all the kids were confident in handing him a carrot. Ol Pejeta regularly hosts education trips for the local community to bring them closer to the animals and teach them about the conservation efforts.

White vs black: the names of the species have little to do with their color - they’re all grey. White rhinos are generally bigger and heavier, but also calmer, a little more social than their black counterpart. The name however comes from the shape of their mouth, an anglicized version of the Dutch “wijd”, meaning wide, representing their wide mouth. This shape is linked to their feeding habit: wide rhinos are grazers, eating grass from the ground in large bites, whereas black rhinos use their much more pointy mouth to browse on shrubs and leaves in bushes and trees.

The Pride

Ol Pejeta is also home to six lion prides with over 70 members, and we saw a lot of them during this sighting, with over 20 individuals resting together in the late afternoon; slowly becoming more active, stretching and scratching, as the sun set.

One of the youngsters also made an attempt at catching some guinea fowl - completely unsuccessful, and even the distant herd of gazelles had long seen him stalking the bird.

As the light faded the large male decided to get up, greet everyone, and ended the shenanigans - they made their way off into the forests and it was probably time to look for today’s meal.

It’s very hard to follow lions at night, but we did spot what I suspect is a Verreaux’s Eagle Owl (the largest African owl) in the grass on our way back.

The next morning…

I can’t say for sure whether the leftover Kudu skeleton this vulture is sitting on is related to the pride going for a hunt the night before, but some predators certainly had a filling meal.

The Reticulated Giraffe

The northern part of Kenya also features a special type of Giraffe - did you know there are multiple species?

With up to 6 meters in height, the Reticulated Giraffe is the largest of them and the tallest land animal on Earth.

Aside from their impressive height, it’s the fur coat pattern that gives away this type of giraffe -the bright lines between the brown patches are much thinner and clearly defined than the common Masaai Giraffe.

They are an endangered species, with about 9000 individuals left in the wild. We got lucky to see a big herd with over 20 or so individuals together.

Melman

The cartoon character from the Madagascar movie is a Reticulated Giraffe, although I didn’t see any of the same tendency to hypochondria in the wild individuals we observed here…

The Northern 5

Reticulated Giraffe are part of the so-called “Northern 5” - give species commonly found only in the northern parts of Kenya and beyond. The Grevy’s Zebra is one of them, and while not common in Ol Pejeta there are plenty in Laikipa. This specific individual is a hybrid between the plains and Grevy’s individual. The brown-ish colour, smaller size, rounder ears and fewer stripes on the belly give it away.

The third Northern 5 is the Beisa Oryx - allegedly there are only three of them in the conservancy, and we managed to get a very distant and very lucky glimpse of them.

The other two members of this elusive group are the Gerenuk (which can actually also be found in other parts of the country including as far south as Amboseli) and the Somali Ostrich, for which you need to go further north.

On the Lion’s Path

The conservancy tracks a few lion prides with collars to observe their movements and health - normally that information is not accessible to tourists, but the park management sometimes offers visitors to join the rangers for lion tracking in the mornings. Despite having seen a huge pride already, this is never something to miss!

And what a good decision it was - we learnt that the collared female was heavily pregnant and probably about to give birth, or may have already done so. That meant she was going to be very difficult to find. A lioness that’s about to have cubs will usually separate from the pride and hide deep in the thickets. Indeed, we spent a couple of hours driving to different areas and listening for the ominous beeping sound on the receiver until we managed to hear anything.

As expected, she did hide far into the thick bushes, and only after half an hour of heavy off-roading (the benefit of being with rangers!) did we manage to come close… but it was all worth it - it turns out, she was not alone anymore.

The lioness had given birth a few days ago - the youngsters had barely opened their eyes. It was the first time anyone had seen the cubs, and even the rangers were surprised. They had expected them in a week or two. We observed a total of four cubs, but they were deep inside a group of bushes and very difficult to spot - I suppose that’s the point, well done to the lioness.

We observed them for a few minutes more and got a chance to see one of the tiny cubs (look at the paw!) enjoying a meal before deciding to leave them alone. A lioness and her cubs are extremely vulnerable to hyena and rival lions during the first weeks after they’re born, and we didn’t want to draw more attention to their location or trigger the lioness to move them, which is always risky.

Another male and female were sleeping not far away in the bushes, which is quite uncommon, and the rangers decided they would not visit them again for at least a couple of weeks to avoid any disturbance. As a result, I’m not sure what happened to this litter.

In a rather sad turn of events we encountered this black-backed jackal on the road on our way back, which had seemingly been hit by a car the night before - speeding is also a problem inside a conservancy. We saw its lonely companion a few hundred meters from the site of the incident - jackals live in pairs and generally mate for life.

On the positive side we spotted this family with a few young pubs peeking out from the burrow a little later. Jackals are always extremely amusing to watch - they constantly give the impression of being up to no good.

Spotted Hyena

Speaking of pubs, we also had the chance to come close to a hyena den with very young cubs, that occasionally stuck their head out, but didn’t seem quite confident enough to come out and play in our presence.

Even the large bone with some leftover meat didn’t seem to be intriguing enough for the small ones - maybe it’s because their survival rate into adulthood is as low as 50%.

Buffalos are common in Ol Pejeta as well - it’s home to all of Africa’s Big 5. They are often the species that suffers the earliest and most during dry seasons, as they rely on constant availability of green grass.

One more species…

A bat-eared fox taking a look at us from its den in the grasslands. These animals with their amusing ears mostly live in social groups, but it seems the rest of his clan was sleeping.

On Foot

I’m never one to miss out on an opportunity to explore the bush on foot - it’s always a very different feeling than in the car. A walk through the area with the local team (including some Maasai from the southern parts of Kenya) was a welcome opportunity.

Brave Souls

While we were well-protected, the local rangers often make their way through the conservancy on foot, with nothing more than a stick to fend off the odd curious animal…

Landscapes

The green bushes and trees along the many small rivers and ponds of the post-rain season make it a beautiful landscape as well - a hint at what was to come in the amazing Laikipia area I was going to visit next.

Mount Kenya

On clear days, Africa’s second-tallest mountain makes an appearance with its various peaks. While not quite as tall, climbing it can be a little more demanding than what it took to summit Kilimanjaro.

The conservancy is a shared environment: wildlife and the local pastoralists live side by side, in what is generally a well-managed and balanced approach. This is not always easy to maintain, as I’ve learned first-hand during my time with the IFAW rangers of the Amboseli ecosystem. Ol Pejeta used to be a cattle ranch and prides itself in its integrated conservation effort, contributing to dozens of community projects from education, food and water security, to energy.

While the cattle traffic is amusing, elephant traffic is obviously a lot more intriguing, especially when a curious youngster wants to inspect your car a little closer.

Ol Pejeta is typically home to a few hundred elephants, but they are not a resident population. Instead, they use the wildlife corridors in the surrounding areas to migrate across the Laikipia / Samburu ecosystem - in fact, all animals are able to freely roam, with the exception of rhinos. Of course this also puts them at risk of human-wildlife conflicts and one of the community engagement aspects is to mitigate and manage these situations to avoid crop raids and similar issues.

As readers of this blog will know, elephants have become one of my favourite animals. I could observe them for hours, particularly the large bulls or family groups with young calves like this one, probably barely a few weeks old.

Mother & Calf

Speaking of calves: We spotted this mother and her young one relaxing in a wide open area, with the characteristic oxpeckers sitting on top of the female.

The Battle

What seemed like an innocent family gather quickly turned intense when two males started to compete for the spot by the female’s side. It’s only when they move like this you realize the force of a white rhino that weighs up to 4 tons and can run up to 60km/h - twice as fast as an average human.

After a short altercation they decided she wasn’t worth the risk of an injury with their huge horns - a white rhino’s horn can grow up to 150cm in length. Despite its impressive shape and size, it’s difficult to understand why a single horn can fetch around 50,000 USD on the black market, when the horns are made of keratin, just like human fingernails. It's this demand that continues to make them an attractive target for poaching.

Sitting not far from the rhinos were two lions, including this magnificently strong individual.

Chimpanzee Conservation

Aside from the rhino conservation work, Ol Pejeta is also home to the Sweetwater Chimpanzee Sanctuary, established with the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) and the Jane Goodall Institute.

Chimpanzees are not native to Kenya, but the 35 or so individuals here are mostly rescued from illegal trade, orphans, or have suffered severe injuries. They are being nursed to health and then join the two groups living in a very large enclosed area in the conservancy.

🌈 Lucky Moments

Although the rainy season had just ended, we barely felt a few drops during our time in Ol Pejeta. On the contrary, the last remnants of the clouds and their contents made for one of the most beautiful moments as a rainbow appeared behind the airfield, where many animals were grazing in the late afternoon, giving me the opportunity for some unique compositions.

One Last Rhino Encounter

As the rainbow faded and the sun slowly set in the other direction, we spotted a black rhino mum and her calf in the distance - a chance for some silhouette photos, if they were to remain calm as we approached. More alert and shy than white rhino, this was not a given. They eyed us cautiously as we positioned ourselves, but luckily felt we were not going to be bothering them, and continued grazing.

We spent almost 30 minutes with the family until the sun disappeared below the horizon, and during this time I managed to take what are probably my favorite images of the trip.

Not wanting to be left out, these two impala posted for another silhouette image just a few minutes later. A beautiful end to the day and my time in Ol Pejeta.

The End

It’s only after you spend dedicated time with these animals and observe them beyond a quick drive-by that you appreciate their behavior and beauty - let’s hope they’ll roam our planet for longer than what the recent trajectory would indicate. I’m sure Ol Pejeta will continue to play a role in this quest, and maybe give us a chance at seeing Northern White Rhinos in the wild again soon.

Subscribe to my newsletter to get notified and don’t miss out on more Wonders of the Globe.

Other Recent Posts:

In Search of a Black Leopard

For several years I’ve been following the journey of a special variant of what is probably my favourite animal - the elusive black leopard.

Ever since reading Will Burrad-Lucas’ incredible book “The Black Leopard” (go check it out, his work is truly pioneering and inspiring) I’ve been keeping my eyes open for sightings of black leopards, so that I could take my chances at seeing one myself. It’s been several years since I had my mind set on finding this melanistic version of my favourite cat in the wild, and Kenya’s Laikipia area seems to be the hotspot in Africa for this rather rare genetic mutation.

Although several black leopards have been spotted here, a specific individual has been rising to prominence in recent years: a female that has become quite habituated around humans, having grown up near a camp.

This presented what is probably the best chance since forever to see one in the wild. In mid 2025 I finally had an opportunity to visit Kenya again, owing to a planned trip to Amboseli National Park for IFAW, and so it was time to make this sighting a reality! It was also going to be a new wildlife photography experience for me, as my sister happened to join for this leg of the trip - clearly, no one can escape the allure of a black leopard.

A Black What?

At this juncture, it might be worth answering a question a few people asked me when I told them I was going to find a black leopard: “Don’t you mean a panther?” - you could be forgiven for thinking so, but actually there is no distinct species called ‘panther’. The blackness is caused by a recessive gene that causes leopards to be melanistic due to an overproduction of melanin. It needs two leopards with this recessive gene to meet and mate for a black cub to develop, making this exceedingly rare. The umbrella term panther is a colloquial description for any black big cat, and also includes black Jaguars - those can only be found in South America and look very similar to leopards, although generally a little bigger.

The journey to the lodge in Laikipia county in central Kenya was a rather short one. I had already spent a few days in the area, visiting Ol Pejeta, one of the strongholds of white and black rhinos in the world, and also home to the two last northern white rhinos on our planet - more on that in a future blog (subscribe!). The drive takes you through a number of farming areas, with an animal you’d not really expect it in Kenya: Camels. They are however kept quite frequently in the north of the country for trade and export.

The Northern 5

Another rather interesting animal we encountered on the way was one of the so-called “Northern 5”, in reference to the local version of the typical African Big 5 animals (did you know there are also the Small 5?): The Grevy’s Zebra. This species of Zebra is a little more shy and taller than the regular plains Zebra, and has thinner stripes that end at the belly. Most notably, it can be recognized by its round Mickey Mouse ears - distinctly different from the Zebras one usually sees.

A second animal that’s part of the Northern 5 is the gerenuk, a long-necked, medium-sized antelope. Frankly, I’ve also seen it in the south of Kenya, which tells you a little bit about how strict the classification of the Northern 5 might be…

Glimpses of Laikipia

As you continue deeper into the wilderness, signs of human evidence fade away, with the incredible landscapes of the area coming into focus: low-lying plains around the Ewaso Nyiro and Ewado Narok rivers, dotted with ancient dryland forest remnants and rocky ridge lines. One of the most incredible bush landscapes I’ve ever seen, more on that later…

There was however some temporary human presence in the area: during my time here, we had several encounters (sometimes visible and sometimes only audible) with the British military, which is conducting troop exercises here every year. Why they need to conduct their field work in central Kenya is anyone’s guess. Speaking to various locals, I have some rather qualified assumptions, based on the post-colonial challenges and conflicts around land leasing that have become more prominent in recent years.

After around 3h of driving we arrived at the lodge in the afternoon and had the chance to speak to the owner of the camp, Steve, who told me that the resident black leopard here has mostly been sighted in the evening. She had two cubs recently (before you ask, unfortunately they’re not melanistic, it’s a recessive trait, and either way they had barely been spotted at all so far), and has been more cautious in her outings, but also more focused on hunting to provide them with their daily meals. That means, sightings during the day would be unlikely, but on the other hand, the chances of seeing her with a kill would go up…

The good news is, we would not have to go far, the leopard’s territory is literally the hill of the camp and a small portion across the river, which she used to cross occasionally. Leopards in Laikipia have relatively small territories, owing to the amount of prey almost year-round - in fact, their ranges overlap quite closely sometimes, as we’d experience first-hand.

We stuck to a clearing near the camp and kept our eyes open, spotting a few elephants that had just come back from a dust-bath in the mineral rich brown soil of the area - some remains of their ancestors could be seen nearby.

As in many private conservancies, off-roading is possible here - and almost necessary for good sightings - and it shows on the land cruiser, which has been modified with removed doors for more freedom during photography.

Darkness arrives quickly near the equator, with a short golden and blue hour. It was my first day and I didn’t have many expectations to see a leopard, let alone a black one, but my (excellent) guides Paul & Francis were confident - our target had been seen for most days in the past week. They suggested we start to make a move through the dark paths around the camp, using the car’s lights and a dedicated lamp to see if we could spot the distinct yellow eyes of the cat - seeing her fur would be hard, given her colour (or lack thereof). We drove for around thirty minutes, more or less in circles, with a couple of other cars from the camp covering the rest of the area to increase our chances. It feels pointless to drive in circles, looking for a black cat moving quietly through the tall grass and bushes in the darkness of the endless wilderness. But this is what makes it special. And special it was.

Giza

We passed a tight curve, and she suddenly made her appearance out of nowhere, crossing the path in front of us: the elusive black leopard, Giza.

With silent but determined steps, carrying what seemed to be a hare in her mouth into the thicket, she had given me the moment I was looking for.

I was too in awe and too slow to get my camera set up for the dim light of the lamp quick enough to capture the moment, but she jumped onto a tree stump and started to devour her catch, giving me the chance to get some photos as she looked back for a moment. She was close to us, which means you could clearly make out the characteristic leopard spots on her majestic coat.

She disappeared into the tall grass once she finished her meal, and I had to catch my breath for a moment to process what happened.

Looking at my images, and learned that I had missed quite a few photos: A fast cat in the dim light of the handheld lamp, moving like a black shadow through tall grasses, really makes for some of the toughest photographic conditions you can encounter - but a few tweaks to the focus setting and exposure behavior should make things better. Now we just had to hope this would not be our only encounter…

Ghost of the Night

My concerns were unfounded. As we followed her through the thickets we could see her stalking a small antelope.

We switched off the lights and engine, and a few seconds later everything was over - a single squeak of her target, and silence again. And then she walked out of the bush, carrying her prey, most probably with the goal to feed the two cubs hidden away somewhere.

We let her wander off in peace to do just that, not wanting to attract too much attention on her, but just a few dozen meters past the car, we heard the distinct sound of two leopards in a brief altercation. We switched on the light, and just saw Giza run off into the distance, as a large male walked into the other direction, carrying her kill away.

Kijana is a strong leopard whose territory just borders Giza’s, and this was seemingly not the first time he took advantage of her predatory skills - his size and the fact Giza has cubs now makes it less likely she would risk an injury and try to fight him off. As we learned over the next days, catching another Dik-dik seems to be the far easier task for her, and it is what she did this time as well: we left her alone, but another guide told us they saw her with a fresh kill a few minutes later. What a first encounter!

One of the reasons Laikipia is such a stronghold for leopards, and why there can be multiple individuals in very close proximity with smaller territories, is the local density of these peculiar small antelopes: Dik-diks. You will see dozens every day, roaming around in the dense bush, and making alarm calls whenever they see or smell or hear something unusual - a great indicator if you’re on the lookout for predators.

Guenther's Dik-dik

The sub-species here has a rather funny looking nose, long, flexible, and bent downwards over the snout. They live monogamously, so you’ll mostly spot them in pairs - which also means that every morning you can congratulate those who didn’t turn into a widow/er the night before…

We spent the morning of day 2 exploring the area - it was unlikely that we’d see Giza again during the day, but there are plenty of leopards around. For now, rich birdlife was on the agenda, with common cuckoo, pied king fisher, bee eater, and even a nubian woodpecker among the sightings.

Laikipia is also home to the largest and probably most striking extant guinea fowl, the vulturine guinea fowl. It typically lives in flocks of about 20 birds.

Although less appreciated by birds, when it’s quiet on safari black-backed Jackals often add some entertainment - this couple was quite chilled and minding their own business though. Laikipia is home to lions, wild dogs, and also striped hyena - all animals I wouldn’t mind seeing - particularly the latter is one of the missing large mammals on my Africa list.

After lunch and an afternoon break from the heat, it was time to head out again and focus on our special black cat. The camps location on a hillside makes for a perfect viewpoint over the incredible scenery here - although it was a relatively dry year, the rainy season turned much of the landscape green. Around October, most of the region will turn brown and dusty again, with very little respite for grazing animals and a consequentially happy time for predators.

As the sun set, some of the camp team are using their binoculars from the viewpoint on the top of the hill to look for signs of Giza.

And this time it was another guide who told us she was out: just as the last light of the day faded, Giza appeared, walking casually past the front of our car - I caught a glimpse. If you look closely, this image also shows the little distinct kink at the end of her long tail, maybe a remanent of an accident, or just another idiosyncratic feature of this special animal.

“Giza Mrembo”

That’s the full name she was given after her birth a few years ago. It means “beautiful darkness” and I couldn’t think of a more suitable name.

After a few minutes of traversing the rocks and long grass, she once again started to stalk for her favourite prey, and once again, it was only a matter of minutes before a quick rustle in the bushes was followed by a high-pitched squeak. A few seconds later, the master huntress appeared with her kill.

The rhythm of the first full day became our routine: exploring the surrounding area in the morning, enjoying the scenery, see what animals we can find, before staying close to the camp and waiting for Giza’s appearance in the early evening. We got lucky and spotted her almost every day, only the rain made things difficult one night. Nightly outings in the bush are always interesting, for instance, we spotted a striped polecat, also referred to as African skunk or zorilla - hard to photograph, so you’ll have to live with this image.

Somewhat more common to see, but still an interesting nightly sighting, was this genet. Related to civets, they have a cat-like body with short legs.

Nevertheless, the daylight adventures were equally as enjoyable, for example watching these rock and bush hyraxes coming out to sunbathe in the morning. Everyone who has ever seen these has probably been told that they are the closest living relatives to elephants and assumed it’s a joke, but well, it’s not, they are.

My knowledge of birds remains very limited, but over the years I slowly began to appreciate them more and more as part of the ecosystem.

We encountered several trees with dozens of weaver nests, such as the one on the left (with soft, green grass built during the wet season) and the Village Weaver on the right, using dry branches to make its hanging nest.

A pair of speckled mousebird on the left, with their characteristic long tail, and two spurfowl to the right.

A long-tailed widowbird in breeding season with its extensive tail feathers, and what I think was a pair of spotted eagle owls, relaxing in the exposed roots of a tree on the eroding river banks.

Like many of the more rural areas that are not national parks, Laikipia is also a mix of conservancies, farmland, ranches, and community lands. That often comes with conflicts, not just among wildlife and humans, but also different interest groups. Settler descendants, investors, ranch operators, and the indigenous tribes are often at odds as to the most efficient use of the land.

Either way, it’s always useful to build a good rapport with the locals around. The herders bring their cattle and goats through parts of the conservancy, and are always on the lookout for predators - helpful for us!

We discussed a new leopard that had been spotted near the river banks in this area, and were able to observe him twice over the following days.

Spot the cat?

The first time was more of a typical encounter: from a distance across the river, in the high grass, with hours of no movement beyond a flapping ear and a quick tilt of the head. Can you see him?

But on the second encounter, this adult male put on a show for us, starting on our side of the river bank and calmly watching a heard of Impala on the other side. After a while, he decided they might be worth a closer look - but that meant crossing the river…

… and that involved a few jumps over several meters, which he made appear effortless and elegant. One reason I love cats. Unfortunately by the time he made it, the impala headed for safer grounds and he just watched them from a distance.

We followed him for a few hundred metres on the river bank, before he decided to lie down exactly in the spot where we had (barely) spotted him the day before - cat routines.

More Big Cats

After a rainy night, we spotted a few prints in the sand - clearly too big for leopards, and definitely also very big for a typical lion: these were of a massive male for sure.

The Laikipa region is in fact also home to a large number of lions, although their density in this area isn’t as high - to the benefit of the leopards. We did spot a female for a brief moment, which, as we learned, had cubs recently - but no signs of them. Admittedly, lions were not my focus.

The Young Male

Instead, the leopard encounters continued beyond Giza - their density in this area is really amazing, and in just a few days I saw more individuals than in all my previous trips throughout Africa (of which there were quite a few).

And what beautiful encounters we had, such as with this pretty young male, who posed for us for several minutes. We had hoped his mother, who is still close by, would join, and we heard a few calls but didn't manage to spot her.

He was a curious fellow, which is to be expected with young cats. On the other hand, you don’t want habituation to go too far, and it’s a fine line between animals seeing the car as being part of their environment and ignoring it, or going a step further and interacting with humans more directly, which is not desirable.

Close Encounter

Did I say he was curious?

We moved away from him at this point to not give him more opportunities to come even closer.

Laikipia Landscapes

Although nothing could top these leopard sightings, the landscapes came close. Of course, the greenery at this time of the year helped, but the combination of rocky outcrops, the river banks, gentle waterfalls, and the endless plains and bushland really made this one of my favorite African landscapes ever.

We spent one morning exploring a few of the outcrops on foot for a better view, hoping we wouldn’t get pushed off the steep ridges by a mean baboon....

Luckily that didn’t happen and we got to enjoy the sprawling plateau, encircled by some of the hills of the Great Rift Valley to the west. The scenery here could have escaped straight from Lion King - incredibly beautiful.

The seeds of some of these palm trees are carried for hundreds of kilometres through the river, before settling on the banks during periods of flood - in turn, elephants then carry their seeds further through the landscapes.

Even if you never get to see a single leopard (hopefully that won’t ever be the case) this area is worth a visit.

My guide couldn’t resist lifting the camera up to capture some of this beauty either.

The Master Huntress

At night though, only one thing was on our mind - more sightings of Giza. And we were rewarded almost every evening. Her hunting prowess and the need to bring home at least two kills to her cubs every day meant that no evening passed where we didn’t hear the characteristic squeal of a dik-dik in distress. For better or worse, it never lasted more than a few seconds, so efficient was the leopard in her attempts.

We can’t know for sure, but it may be her black coat that makes Giza a more efficient predator at night, even more difficult to spot, and reversely also the cause for her to develop a preference to hunt in complete darkness - indeed, the brown bushland is not a very suitable environment to stay undetected during the day if you look like Giza.

Patterns

In the right light and angles, her coat truly shone, literally and with its intricate black pattern.

With the Boss

On our last day we had the pleasure to be guided by Steve, the lodge owner, himself. That was a privilege, as his experience in the bush of this area is unmatched, and we also got to chat a bit about his time in Zimbabwe - for example, he happened to know the amazing Steve Edwards of Musango, and Barry of Chewore. Read about my time at their lodges, standing in dinosaur footprints (yes, for real) and taking one of my favorite images ever.

I always love being out in the bush for a walk as well, so we went for a morning trek along one of the river banks - it’s just such a different feeling compared to being in the car, and I can recommend it whenever you have the possibility.

Over the last years I’ve developed a soft spot for elephants, and Steve took us with him on foot to see this family cross the river, forcing their youngest to become a temporary submarine.

He also showed us these makeshift beehives the locals hang from trees to encourage honey production. However, this is a tricky endeavor: honey badgers often outsmart even the most stable human construction and manage to climb down the ropes and open the wooden boxes, as seems to have happened here with a few of them.

Back in the car, we decided to venture out a little further into new areas of the conservancy and beyond - only a few roads were off limits due to the military exercise: Hatari! (That’s danger in Swahili, and also the name of a classic 1962 movie with John Wayne everyone who loves Africa should watch!)

We spotted another leopard who had just hunted a hyrax - once again, observing the prey is often the best way to make out the predator. A group of rock hyrax seemed very agitated and made alarm calls, which gave away the presence of the cat. He hid in the tall grass with his meal, giving us only a brief moment to make out that he was a shy individual, less commonly seen.

Striped Hyena

We also managed to tick off another of my goals for this trip - seeing a striped hyena. They are more common in the northern half of Africa, the Middle East, and parts of India, whereas their spotted and brown cousins as well as the aardwolf (the latter two still on my list) are more frequently seen in the southern half of the continent. They are shy animals, and we had to be quite strategic to get these images before it disappeared into the bush - Steve’s knowledge of their behaviour paid off.

There are around 10,000 individuals left in the wild, primarily nocturnal and mostly observed alone or in pairs (they are monogamous), unlike the spotted variant, which is usually found in groups. They are heavily featured in folklore and mythology in the Middle East.

The Last Morning

In the early hours of my final day, we launched an attempt at finding the local pack of wild dogs - another amazing underrated African mammal species.

One of them is collared, so the radio would increase our chances of finding them. It still depends on line of sight, and with the many ravines and a dog that may be sleeping in one of them, it’s still a challenge.

Too much of a challenge for us this time, as even after several attempts we didn’t get a signal.

Instead, we were blessed with a final leopard sighting. It was a distant one, but a very interesting observation. The cat moved close to a giraffe, which watched him very carefully (although leopards don’t really pose a threat to them), and a small group of waterbuck (whose young might be a risk).

Can you spot it? It’s testament to the Steve’s observation skills that he was able to determine the presence of a leopard by the watchful alert behavior of the other animals, from several hundred meters away - while driving.

One last amazing bird sighting was this martial eagle - with a wingspan of over 2 meters and almost 1 meter in length, this is Africa’s largest eagle. An apex predator, but by now unfortunately endangered due to habitat loss.

The Queen of the Darkness

It goes cats -> leopards -> black leopards - we reached the end of the funnel of my favourite animals, it doesn’t get much better than this.

One can only hope that Giza will be with us for several years, and produce more offspring. With some luck, we might get to see a few more iterations of a beautiful darkness in the area, given the presence of the gene in the local leopard population - I’m here for it.

For now, it’s a true privilege to get to see a rare animal like this in the first place, and even more so to observe her up close. It may sound corny, but there is undeniably a certain aura around her beyond just the color of her fur, although one might be the antecedent of the other.

Subscribe to my newsletter to get notified and don’t miss out on more Wonders of the Globe.

Other Recent Posts:

On a Mission for IFAW - Elephants & Rangers

My second trip to Amboseli National Park in collaboration with IFAW and Pexels, documenting the amazing ecosystem and the people protecting it.

In 2024 I came across a competition on Pexels’ website titled “Our Wild World”, looking for impactful images of our earth’s flora and fauna. There are lots of photography competitions out there, but this one intrigued me for two reasons: first, it was fittingly organised in collaboration with IFAW, the International Fund for Animal Welfare, a large conservation non-profit with activities all around the world. Secondly, the first prize was a trip to Kenya’s Amboseli National Park – a place I had visited before and that will always be dear to me owing to its incredible elephant population. Most notably, its group of rare Super Tuskers: elephants whose tusks exceed 100 pounds each, often reaching all the way to the floor.

Within a few minutes I had selected and submitted some of my favourite images, among them also one taken in Amboseli itself a few years earlier, showing one of the most famous Super Tuskers: Craig, the elephant said to have the largest tusks in Africa.

Not expecting much, I received an email a few weeks later, telling me this specific image had won the competition! I was delighted, of course, but the irony that a photo from Amboseli was the reason I won a trip to Amboseli was not lost on me. It had escaped the Pexel’s team and judges until I pointed it out to them later, when I shared a few quotes and we had a short video interview about the photo and its behind the scenes - watch the result here.

On my call with them to discuss the award a few days later, it came to me that a simple tourist trip to Amboseli would be enjoyable, but not provide much meaning for IFAW, Pexels, the elephants, and myself as well. Why not try to do something that serves a bigger purpose and aligns with the vision of the competition and its organisers? Luckily both Pexels and the IFAW team thought that was great idea, and were fully on board to help fund and organise a longer trip that would not only give me the chance to visit the Amboseli National Park and see its wildlife again, but go a little deeper into the local conservation effort and its challenges. To achieve this, I’d be visiting the IFAW offices in Nairobi, and then spend time to shadow and document two of IFAW’s most important ranger bases in Amboseli. Of course we’d also launch an attempt to find Craig and the other Super Tuskers, and cover the wider ecosystem with the camera.

In Nairobi

Following a few months of planning and organising, the time had finally come. On May 26th I arrived in Nairobi, having already spent two weeks in Kenya’s Laikipia and Ol Pejeta areas in the north (blogs coming soon - amazing sightings). I started the day with a short visit to Nairobi National Park with its iconic juxtaposition of wild animals framed by the city’s skyline

The Ivory Burning Site

Created in 1989, this site near the entrance of the park stands as a symbol against the ivory trade. Kenya’s presidents have overseen four burnings of seized tusks, the last one included 105 tonnes of ivory in 2016. It’s now a conservation memorial and a picnic spot. It gave me some goosebumps to think how many elephants died for what is now a pile of ash, and it’s a stark reminder that being able to see them in the wild is not to be taken for granted - it needs work.

A quick stop at the Sheldrick Trust, which saves, raises, and re-homes orphaned elephant and rhino calves, as we exited the park. Nothing better than watching some baby elephants fight for milk to contrast the somewhat haunting images of the burned ivory site.

I made my way to the IFAW office in the afternoon, where I met Guyo, Communications Officer for East Africa, for a discussion on logistics and footage we were hoping to get - as much as that’s possible given the wildlife involved and the unpredictability of the African bush!

To get you into the mood for this rather long blog, here’s a 2 minute video of some of the highlights that are about to follow…

After a 5am start the next morning, I was on the way to Wilson Airstrip for a short flight eastward, heading to the airstrip of Amboseli National Park at the foot of Tanzania’s Kilimanjaro mountain – the iconic backdrop of the park, and also my next destination, as I planned to climb it in early June.

Old Friends

After landing, my first happy “sighting” was Dickson, one of the best wildlife guides I’ve ever worked with, and who had gladly agreed to help me again during this visit – his network of contacts across rangers, local Maasai, and other guides was invaluable for what we wanted to do. In addition, he had also been working for months to secure us an off-road permit in the park, greatly increasing the chances for unique sightings and photographic angles.

To complete the paperwork for that, we stopped at the Kenya Wildlife Service headquarters and then straight away made our way out into the plains, bushes, marshes, and lakes of Amboseli and its surrounding areas. While we were able to plan when to visit the ranger bases, it’s more difficult to make plans with the wildlife (insert corny joke about sending a meeting invite to Craig). Nevertheless, I had high hopes that during the 5 days I would be able to spend here, at least a glimpse of Craig would be achievable. During my previous visit, it took 3 days of searching and coordinating until we finally got a message that he had been seen in a conservancy outside the park. While elephant herds often follow a routine, lone large older bulls are not as predictable: they can roam over thousands of square kilometres, not stopped by park boundaries or even national borders.

A Reunion with Craig

Let me cut this short – my worry about whether I’d be able to find Craig again this time was luckily unfounded. In fact, I could not believe what occurred – just a few hours after landing on the airstrip, I stood in front of him again, gently walking towards the marsh, watching him enter the water for a drink and some fresh grass.

While his figure is in fact not among the largest elephants in the park, it’s his tusks and the gentle, yet imposing presence that truly makes you feel in awe when watching this magnificent animal. At 53, Craig is no longer a youngster, has seen and done it all, and is not fazed by human presence. His age also means that there is not much time left for him: aside from poaching, disease, or other unnatural deaths, elephant lifespan is primarily dictated by their molars. With six sets lasting 10 years each, it’s usually in their 60s when they’re unable to chew anymore and face starvation. As we left him alone for the morning and made our way to the lodge, I felt a sense of relief and gratitude that I already had been able to document him again so early in my trip. Even before my first trip to Amboseli, I enjoyed seeing elephants in the wild, but observing them up close here has given me a new level of appreciation for their complex social structures, intelligent behaviour, and sheer size, but also the threats and difficulties they face.

Day 1 was not over yet. In the afternoon, Amboseli had another beautiful sighting in store for us: a cheetah. But she was not alone. This cheetah gave birth to a total of five cubs several months earlier, all of which she has kept alive until today, despite the threat of lions and hyena. Can you spot them all?

Although they are slowly approaching full adult size, they still rely on the mother for food and hunting guidance.

We watched them cross the plains and take a short break on a fallen tree, scanning the environment for what might be their next meal, before they disappeared into the thickets. The ecosystem here supports a healthy and stable cheetah population, although the species as a whole has been under pressure from human impact on its range, and is considered the most vulnerable of the big cats. There are less than 7000 cheetah left in the world, spread over only 10% of their former range.

We happen to come across them another time on our second day, giving me a few more opportunities to capture their elegant lean shapes in the tall grass as they stalked a herd of gazelle.

This year luckily brought the significant water needed to sustain the ecosystem. In the past, droughts have been quite severe, resulting in the deaths of many elephants and other species from competition for water. Even today, water access is a challenge as human needs conflict with the requirements of the wildlife – an elephant needs to drink up to 200 litres per day, for instance!

Clouds and a bit of drizzle also accompanied this afternoon, but it made my second encounter with Craig even more special. We spotted him in the distance not far from where he had been roaming around in the morning, when I saw a faint rainbow in the eastern clouds. Dickson and I rushed to him with the hope we’d be able to get a special photo. We only had a few minutes, and at first Craig didn’t cooperate, showing us his backside… but our patience was rewarded when he turned to the side, and I could snap a few images with him and the last glow of the rainbow. You never know what nature has in store!

The last light faded, rains appeared on the horizon, and we made our way back to the lodge.

Team Lioness

For Day 2, we planned an early morning start, heading to the north of the National Park into the surrounding community lands. The goal was one of IFAW’s most well-known ranger bases: the home of Team Lioness, an all-female ranger team, which began its duty in 2019 and now consists of 17 members in total. Its story is a special one for several reasons: the members are often the first women in their families to secure employment, and at the same time break the mould of a traditionally male-dominated domain, taking on the role of protector against poaching and mitigator of human-wildlife conflict.

On Patrol

One of their ranges gave me a short briefing on the day’s activities: typically, they wake up at 6:30, followed by exercise and morning tea, and then a patrol, during which the team reports back findings to the headquarters. They normally walk for 20 km per day, but were happy to cut their route a bit shorter that day – lucky me, it was hot.

The first interesting observation? Two male rangers stayed behind, taking care of one of the Team Lioness member’s young child – unexpected gender role reversal indeed. Evelyn tells me it’s great for her to be able to go to work while knowing that her young one is safe at the base.

As we explore the area, Leah shares that they look for tracks to identify animal activity, with the goal of determine the number of animals moving in the conservancy, and any sick animals or other unusual signs. I watched them map wildlife sightings, and communicating findings using GPS coordinates over the radio to the central base of the area. We spotted zebra, gerenuk, giraffe, and other wildlife from a distance – it’s not common to run into the more dangerous animals such as buffalo or lion during the day, but Team Lioness is not allowed to carry weapons with them (only the Kenya Wildlife Service has the permission to do so), so you always need to be on high alert. Nevertheless, walking through the bush on foot is a very different and much more intimate experience than in a Safari vehicle, and brings you much closer to nature.

I had the chance to spend a little bit of time with them after the patrol, and they revealed some of their motivations for becoming a ranger, hurdles they faced in their communities, and goals for the future. Leah says she wants to pass the knowledge she gained working for IFAW to her kids so that they would also be interested in preserving wildlife for future generations. Human-wildlife conflict is one of the biggest challenges she sees in this goal, as it is a constant struggle to prevent and mitigate the consequences of lions seeing herds of goat or cows as prey for instance, while keeping the communities positive about wildlife, which is critical to its protection. I didn’t know it yet, but we would see an example of this issue first-hand a few days later. I asked her what her favorite animal is - which was probably not a very creative question –and unsurprisingly, the answer was Lioness, because “she’s a hardworking woman”.

One of their newest members, Doreen, is just 24 and joined the team in January. Over a cup of tea, she tells me the reason she joined was to protect the wildlife and culture of her homeland, and it was something that she already cared about back in school. After some jobs in retail and hotels, she found out about the chance to join Team Lioness. She didn’t face a lot of reluctance from the men around her, but they told her the work would be hard. She laughed as she tells me that actually, she finds it “quite easy and enjoyable”.

Although it’s difficult to connect with people in just a few hours, and admittedly many members of Team Lioness are quite reserved (who can blame them, they became rangers to protect wildlife, not to be interviewed by me), I was still happy and grateful they let me into their routine. We shared a few moments of laughter, and I gained some insights into their motivations and goals, and a better understanding what it means to be a female IFAW ranger on a day to day basis.

Here is a short video IFAW and I created with a few more clips of my visit to Team Lioness - inspiring!

The Allure of the Tuskers

Aside from my time with Team Lioness, the day brought with it two more big “Tusker” sightings: elephants of the name of Per, and Wickstrom (they are named by the Amboseli Elephant Trust, but don’t ask me how they come up with these names…).

For Per, it was a beautiful morning sighting on our way to Team Lioness, watching him slowly wake up and start his day. Once you spend more time with these elephants, it’s also easy to see how different they look: Per has a more sturdy, wider figure and head than Craig for example, and his eyes are set deep with large black borders, giving him a mix of scary and sad appearance at the same time.

In the afternoon, the clouds lifted for the first time, revealing Amboseli’s famous backdrop – Kilimanjaro, Africa’s tallest mountain. While it’s situated within Tanzania’s borders, it’s undeniably (for me anyway, having stood on both sides and a few days later, also on the summit) Kenya that got the better view of the iconic flat top with its (ever shrinking) glaciers. As the mountain appeared in the background, our goal became to combine Amboseli’s incredible elephants with what is probably Africa’s most typical fauna, the Tortilis Acacia, and the iconic landscape – a postcard photo.

Just as the day ended after a couple of hours looking for this exact scenery, things came together when I spotted a big elephant in the distance, slowly approaching a beautiful acacia tree to scratch his skin. We rushed through the bumpy thickets, positioned ourselves, and managed to take some images. Wickstrom has beautiful symmetric tusks, and at age 42, he’s in his prime. A true privilege to see him under these conditions.

Day 3 - Above the Clouds

The next day started very, very, early, but for good reason – it was time to see this ecosystem from a different perspective. The plan to do that? A balloon flight. Leaving the lodge around 4am, I headed to the boundary of the park, with the hope to explore the landscape from above. The evening before was cloudy and windy, so this hope was slightly diminished given that the weather conditions around Kilimanjaro are often unpredictable.

And indeed, as we left, not a single star was visible, making it clear to me that a thick cloud layer put the chances for a beautiful sunrise and a great view of the mountain into question. However, my experience with cloud conditions and flights (balloon, helicopter, drone, or otherwise) told me that sometimes a less promising outlook holds opportunities for something special. It would turn out that I wasn’t wrong, but as we watched the balloon inflate and then climbed into the basket around 6am, the thick cloud cover I had suspected was confirmed as daylight crept in.

We gently rose into the air and came closer and closer to the white ceiling above us – until we were fully engulfed by what seemed like white, cool, humid smoke. Seeing absolutely nothing when looking around was of course not why you’d fly in a balloon, but the temporary blindness only lasted a few seconds.

At this point, we breached the cloud layer at an altitude of around 6000 feet, and it was like entering another world: the magical sunrise on one side, and a clear view of Kilimanjaro above the clouds on the other, with the snow-capped peak illuminated by early rays emanating from our home star. I have been lucky to experience many beautiful things in life, but can’t deny that this brought a smile on my face.

It was another sign that sometimes it’s ok to let nature do its thing and embrace what you get, rather than trying to force it, a lesson I also try to apply to wildlife encounters (but sometimes struggle with in other parts of life 😃).

Our pilot (and my hunch about the local weather conditions) told me that it’s not uncommon to be able to have this experience, but it’s by no means a given: there are plenty of clear days (which are beautiful of course, but a little less interesting) and also days with heavier cloud cover or stronger winds that don’t allow the balloon to simply pop up above the cloud layer. As we dropped below the white blanket again the sun also made an appearance over the landscape for a few moments, and we descended over the Maasai bomas (villages), their cattle, kids going to school, and a few animals as well: hyena, giraffe, wildebeest, zebra, gazelle, and ostrich could be spotted from the air.

After another half an hour of quietly (this is one of the things that makes balloon flights special) hovering over Amboseli, it was time to land before we got close to the nearby mountain ridges. A small bump into the tree canopy and a few bumps over some bushes, and we were back on the ground.

After a short drive back and the obligatory balloon champagne celebration (non-alcoholic for me), we encountered a beautiful large herd of elephant crossing the road towards the marsh from the forest area, and I spotted a female with very large tusks, as well as some juveniles engaging in playful behaviour. Making a mental note to ask Dickson about the female later, it was time to head back to camp.

For the afternoon, we had a decision to make: Craig was spotted on the other side of the park in the morning, but so were some lions. It’s hard for me to say no cats of any kind, but as there were glimpses of Kilimanjaro between the clouds and one of the photos I was still looking for was the iconic view of Craig and the mountain, there was only one right choice to make: you can never go wrong with spending time with this creature, it’s almost therapeutic to watch him go about his business. Although that business didn’t quite include plans to face the right way for the Kilimanjaro photo, we got quite close to what I was looking for, with two egrets adding to the show. These birds follow elephants in the hope that their movement stirs up insects on the ground, which they can then feast on (one reason elephants are sometimes called the ecosystem engineers).

Real Human-Wildlife Conflict

We planned our second ranger base visit for the morning of Day 4, heading to the north of the park into the Illaingarunyoni Conservancy, where IFAW opened a new base in 2023.

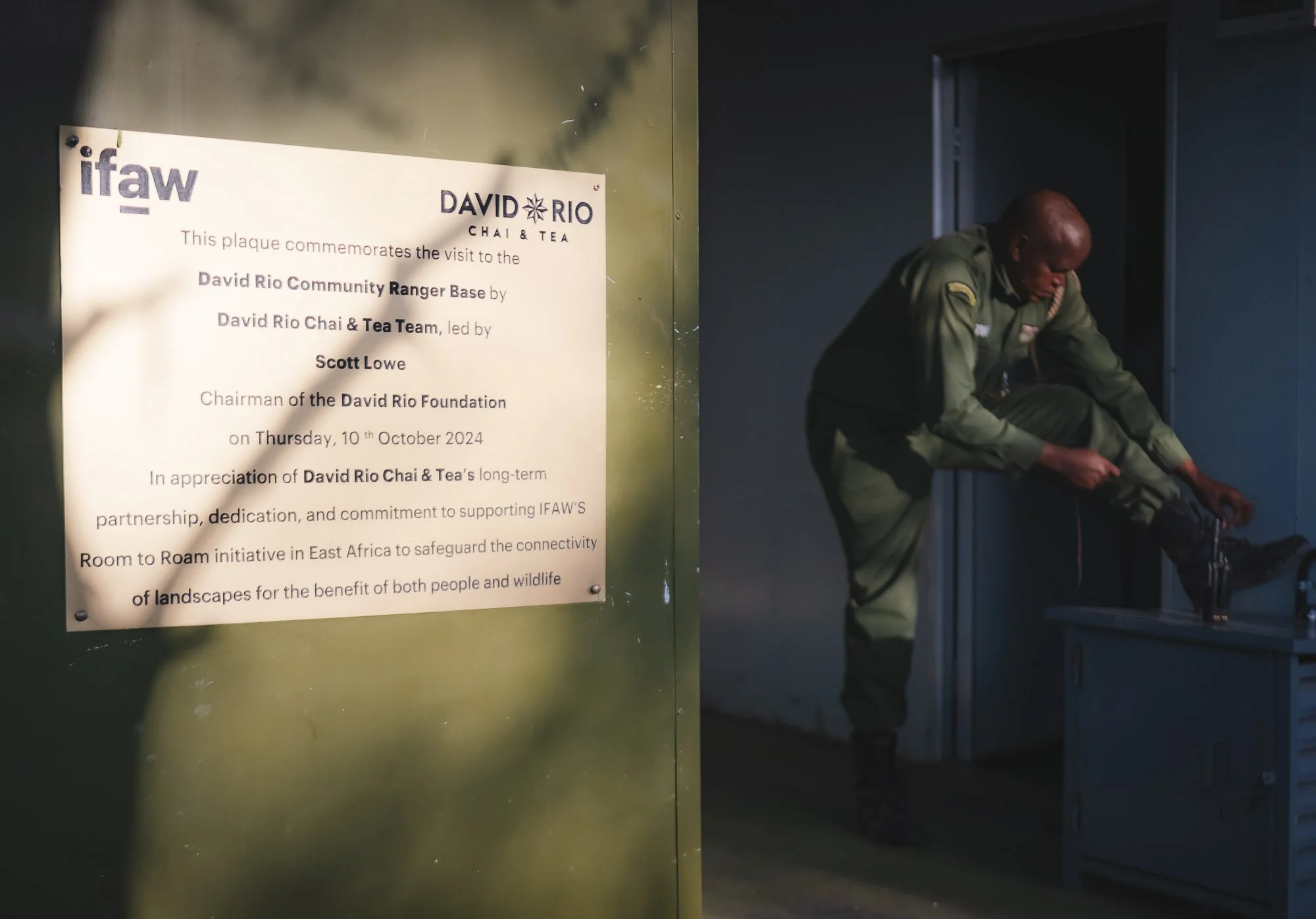

This base is named after and was established in partnership with David Rio, a chai tea company from the US – a rather unusual collaboration, but their foundation has been active in the area for many years. These partnerships are invaluable for IFAW’s work here, which is not only limited to set up a ranger base and help manage human-wildlife conflict. Leasing land and working with government, researchers, and local communities as well as the landowners (in this case through a formal agreement with the Olgulului-Ololorashi Group Ranch) to establish animal corridors and ensure there is sufficient space for wildlife to move around is another key activity.

One such project is IFAW’s “Room to Roam”, a visionary approach to conservation established across different parts of Africa with the goal of secure elephant migration paths and habitats, while considering the needs of the local community, sharing land and resources. This is not an easy task, and we got to experience why first hand during my visit.

But one thing at a time. We arrived at the base in the early morning, and had the chance to see the team of rangers get ready – only men this time. Moses, the head of the group here, gave me a quick introduction, and then checked in with the rangers in the area if there was any news – funnily enough, we heard the voices of Team Lioness on the radio!

Indeed, for today there was a rather unusual incident that required their attention: a male elephant had been raiding the crops of a nearby Maasai village over the last days, culminating in a major incident the evening before our visit: the elephant turned over a car. The ranger team was planning to visit the incident to understand what happened, and how to deal with the problem, but they did not have a car available to themselves – a major constraint in their day to day job.

Dickson and I had a solution: we offered to take them in our Land Cruiser, and they happily agreed, so after some morning tea and a briefing, we all headed out together. While on the one hand this was possibly a serious incident, it would maybe give me the chance to observe a real life example of human-wildlife conflict.

On the way I had a chance to ask Moses a few questions about his life as a ranger and why he chose to get into this profession. He started 10 years ago, primarily with the goal of support his family and four kids. But he quickly learned that there is more to the job than just subsistence, and it became a mission for him to protect the wildlife. In his words:

“when the animals disappear, our children will not see how we see”.

But it’s been challenging, as they often lack the resources to intervene effectively. Our case was a prime example, as he tells me they would have been able to move to the incident much earlier if they had a dedicated car. According to him, this kind of human-wildlife conflict is one of the primary challenges they face: for a lion, killing a cow is survival for a few days, but that cow is also the source of income guaranteeing food on the table for a local family, or education for their kids – it was a familiar topic to me by now.

As we arrived at the Maasai boma, the rangers first checked in with the village head if I was allowed to enter and take photos – not a given in the protective Maasai community. Luckily, they had no objections, and we joined the discussion of the group and learned a few more details: the head of the conservancy had sent his three sons in an (IFAW-sponsored) vehicle to the affected boma.

They attempted to scare off the elephant with the car, and chase him out of the area. The bull however had none of it, attacked the car a few hundred metres from the field, and turned it over, injuring the occupants, who fled the scene. Luckily the injuries were relatively minor - especially given the state of the car on the photo I was able to see, this could have been much worse.

They showed the rangers and myself the crops that the elephant had raided. It was a very large area, around 1 acre, almost completely trampled and emptied of whatever vegetables and fruits were growing there, mostly tomato. That’s a major problem for the local community, and they were visibly upset.

We then wanted to head out to the scene of the car being turned over, but around half way were stopped as the Kenya Wildlife Service approached. IFAW’s rangers facilitate, monitor, and support, but the KWS is the only organisation allowed to carry guns, and make decisions about wildlife. As their vehicle arrived, more people showed up, and a larger discussion ensued. My understanding was that the Maasai were advocating for the elephant to be killed, while others proposed he'd be chased away and moved from the area.

What happened?

These decisions are not clear cut. An elephant who encroaches on settlements regularly and acts aggressively is a real threat, not just directly to the affected local community, but by extension also through the risk that his behaviour might spread to other elephant herds, creating a larger issue. From what we understood, this bull was migrating from the Tsavo ecosystem, where many elephants are less calm and not as relaxed around humans as here in Amboseli, where conflict is less common. In addition, inaction on the KWS’ part might trigger self-justice by the Maasai, who are fierce warriors: killing an elephant with spears is not beyond their realm of ability, at great risk to themselves and with a painful death for the animal.

Even more so, it would foster a general animosity to wildlife and a distrust towards the organisations protecting it, as they might be seen to disregard community needs, making future collaboration much more difficult. Within these discussions, it became clear to me that my presence, especially with a camera, was not completely without controversy – the typical fate of a documentary photographer and (so I’d imagine) even more so of a journalist. Simply being there as an outsider could alter the behaviour of the people.

This might not be for nefarious reasons - one can imagine a wide range of motivations: the Maasai may not want to be negatively portrayed as advocating to kill animals in western press, or the KWS may think that without outsiders, stakeholders would act more rationally and not try to prove anything. I can only speculate what ultimately triggered the decision to ask us to leave.

Either way, not wanting to aggravate the situation, Dickson and I sadly made our way back before seeing the vehicle or understand the next steps. But not before sharing our thanks to the David Rio Ranger team, and of course exchanging the obligatory selfie and contact details. At this point, we didn’t know what the outcome of the situation would be, but had hopes we might find out later.

As we left, I realised once more the complexities of the overall system that organisations like IFAW need to work in, and the many decisions and opinions that cannot be simply reduced to black and white, even though that is sometimes the way it is superficially portrayed in news on social media, for instance.

A Final Moment with Craig

Back in Amboseli, the afternoon gave me a fourth and final encounter with Craig as he made his way to the northern end of the park, most likely crossing into a conservancy where he’d be much more difficult to find over the next days. Once again, we had plenty of time alone with him while he was feeding and slowly moving from bush to bush, giving me the chance to observe him from the ground, kneeling in front of the car as he calmly walked by. Having experienced what it’s like to be completely exposed as a three-and-a-half metre, five-tonne elephant with two-metre long tusks passes you so close that you could touch him, I’ll always see these creatures in a different light.

There is no way to develop the same respect for their presence from the elevated safety of a vehicle, or in front of a fenced zoo enclosure. There are very few places in the world where it is imaginable to be so close to a wild elephant without danger, or without triggering their curiosity and thus altering their behaviour – something an ethical observer should avoid whenever possible. Craig’s calm demeanor around vehicles and people is what makes this experience feasible, but a wild animal will always remain a wild animal, and should be respected accordingly – there is no guaranteed safety, as we had seen first-hand at the ranger base in the morning. In the same vein, I have unfortunately also experienced how some guides would push their cars into Craig’s path at the last second to get the best close up view, and it makes me increasingly angry to witness this – it’s almost a personal affront, a cringeworthy feeling that makes you want to apologise to this majestic animal for being part of the human species. How much of this must he have endured over his 53 year lifespan, and yet he’s still accepting our presence?

It was these mixed emotions, and the lasting impression of the morning, that we let Craig disappear into the distance, hoping he’d stay out of trouble. In fact, one worry that is always present here is that males like him would cross into Tanzania, where they are less protected, and human wildlife conflict and especially trophy hunting in the Enduimet Area of Tanzania has cost many elephant lives, including several large tuskers in 2023 and 2024.

The Amboseli Elephant Trust has been advocating to end this with some success for more than 30 years, but it seems policies have changed over the last years and the moratorium on hunting in the area was lifted. This is a major issue for the elephant population, as bulls enter their most active reproductive years in their 40s – an age many of them don’t reach.

Let’s hope Craig won't be next.

We spent the last hour of the day reflecting on this, soaking up Kilimanjaro views with wildebeest and waterbucks as the sun set behind us.

Day 5

Although I said goodbye to Craig for this trip, that didn’t mean that my time looking for elephants was over. Remember the female with the large tusks? I wanted to try and see her again, so we headed out early in the morning towards the east, where she’d typically cross from the forest into the marshes, often accompanied by a few large family groups. Just after the sun rose, we did indeed spot her where expected – elephant families have very specific routines they generally follow. It was a clear day, and that meant it was time for more images with the beautiful Kilimanjaro backdrop.

Hollie

Hollie is actually rather small in terms of body size, even for a female, but her tusks are seriously impressive and beautifully symmetric. More often than not, one tusk is used significantly more than the other (depending on whether the elephant is right- or left-tusked, if you will) and that also means they don’t always face exactly the same way.

She also has very large ears, shaped like the map of Africa, and with a distinct cut on the left one. Aside from the wide ears, her body also seemed wider than normal, which could indicate a pregnancy – wouldn’t it be amazing if her and Craig could produce a few more Super Tuskers… let’s hope for the best.

We had a few more beautiful observations of her family group passing through the savannah on their way to the marshes, and also ran into one of the most famous elephant researchers in the world, Cynthia Moss, who was observing them and making notes of their movements. She has been studying the elephants of Amboseli for five decades, and is the founder of the Amboseli Elephant Research Project and its associated Trust. Her books “Portraits in the Wild” and “Elephant Memories: Thirteen Years in the Life of an Elephant Family” are certainly going to be one of my next reads.

The afternoon was spent slowly, exploring more of the fauna and flora of the region. Amboseli is home to 400 species of birds, 80 types of mammals, and 300 plant species, aside from its gorgeous landscape.

The morning of Day 6 marked my last few hours in the park, with an early drive towards the border crossing with Tanzania. I was going to climb Kilimanjaro, after looking at it many times over the last days, mostly with mixed feelings of awe, respect, and excitement.

The Tarakea border is just over an hour from the gates of Amboseli National Park towards the Tsavo region, Kenya’s largest protected area. Of course, nature had one more beautiful morning elephant sighting for us in store before we made our way to the KWS Headquarters again to finish the paperwork required to leave.

I received this photo of the car the elephant had turned over. They’re strong animals…

This is also where I learned of the fate of the elephant that had been raiding the crops in the conservancy where the David Rio ranger base is located: the KWS ranger transparently told us that the decision was made to eliminate him. While this is a sad outcome of the story in one way, for the reasons I mentioned earlier, it may ultimately be the most beneficial long-term option for the ecosystem as a whole, and the growing number of elephants and continued thriving biodiversity in the area with limited conflict serves as evidence to confirm this hunch.

Yet, it’s a stark reminder of the difficulty conservation organisations face, and at the same time clearly shows their importance. Ultimately, it made me appreciate the time I spent in Amboseli and the opportunity to document it with such deep access to its inner workings even more. But now it was time for the next adventure, I had a mountain to climb – and can imagine that this is also a good metaphor for how the task to protect our wild world must feel for organisations like IFAW.

Subscribe to my newsletter to get notified and don’t miss out on more Wonders of the Globe.

Other Recent Posts:

Patagonia - Pumas & Peaks

The Chilean side of Patagonia is home to incredible landscapes and wildlife, and I spent a week here to document some of it during the winter months.

In August of 2024 I finally embarked on a trip to one of the last regions on earth I had not explored at all: South America. The first blog posts are in: Tales of the Atacama Desert and the Wildlife of the Pantanal. There is more to come, and this is the third post covering my trip to Brasil and Chile: The beautiful mountain landscapes of Patagonia, and one of the incredible animals that inhabits them…

From Puerto Natales to the Peaks

I arrived in the small city of Puerto Natales from Santiago (with a short stopover, there are barely direct flights in the winter time), but didn’t spend much time in town, other than a short photography walk to the shoreline with my great expedition guide Rodrigo and his wife, who were to become friends with a lot of laughs on the following days.

Puerto Natales was formally founded in 1911, but its history goes back further than that, with Spanish explorers making visits to the area in the early 16th century in search of the Strait of Magellan and indigenous people having occupied this remote part of the world. First human evidence dates back more than 10,000 years.

Two black-necked swans with the Hotel Costaustralis of Puerto Natales in the distance. My actual destination here was the Torres Del Paine National Park, around 100km to the north, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (one day I should make a list of which ones I’ve seen…).

Torres del Paine

As we drove towards the park, the namesake mountain range came into view, with a beautiful sunrise awaiting at the Amarga lagoon.

Calm Waters