On a Mission for IFAW - Elephants & Rangers

In 2024 I came across a competition on Pexels’ website titled “Our Wild World”, looking for impactful images of our earth’s flora and fauna. There are lots of photography competitions out there, but this one intrigued me for two reasons: first, it was fittingly organised in collaboration with IFAW, the International Fund for Animal Welfare, a large conservation non-profit with activities all around the world. Secondly, the first prize was a trip to Kenya’s Amboseli National Park – a place I had visited before and that will always be dear to me owing to its incredible elephant population. Most notably, its group of rare Super Tuskers: elephants whose tusks exceed 100 pounds each, often reaching all the way to the floor.

Within a few minutes I had selected and submitted some of my favourite images, among them also one taken in Amboseli itself a few years earlier, showing one of the most famous Super Tuskers: Craig, the elephant said to have the largest tusks in Africa.

Not expecting much, I received an email a few weeks later, telling me this specific image had won the competition! I was delighted, of course, but the irony that a photo from Amboseli was the reason I won a trip to Amboseli was not lost on me. It had escaped the Pexel’s team and judges until I pointed it out to them later, when I shared a few quotes and we had a short video interview about the photo and its behind the scenes - watch the result here.

On my call with them to discuss the award a few days later, it came to me that a simple tourist trip to Amboseli would be enjoyable, but not provide much meaning for IFAW, Pexels, the elephants, and myself as well. Why not try to do something that serves a bigger purpose and aligns with the vision of the competition and its organisers? Luckily both Pexels and the IFAW team thought that was great idea, and were fully on board to help fund and organise a longer trip that would not only give me the chance to visit the Amboseli National Park and see its wildlife again, but go a little deeper into the local conservation effort and its challenges. To achieve this, I’d be visiting the IFAW offices in Nairobi, and then spend time to shadow and document two of IFAW’s most important ranger bases in Amboseli. Of course we’d also launch an attempt to find Craig and the other Super Tuskers, and cover the wider ecosystem with the camera.

In Nairobi

Following a few months of planning and organising, the time had finally come. On May 26th I arrived in Nairobi, having already spent two weeks in Kenya’s Laikipia and Ol Pejeta areas in the north (blogs coming soon - amazing sightings). I started the day with a short visit to Nairobi National Park with its iconic juxtaposition of wild animals framed by the city’s skyline

The Ivory Burning Site

Created in 1989, this site near the entrance of the park stands as a symbol against the ivory trade. Kenya’s presidents have overseen four burnings of seized tusks, the last one included 105 tonnes of ivory in 2016. It’s now a conservation memorial and a picnic spot. It gave me some goosebumps to think how many elephants died for what is now a pile of ash, and it’s a stark reminder that being able to see them in the wild is not to be taken for granted - it needs work.

A quick stop at the Sheldrick Trust, which saves, raises, and re-homes orphaned elephant and rhino calves, as we exited the park. Nothing better than watching some baby elephants fight for milk to contrast the somewhat haunting images of the burned ivory site.

I made my way to the IFAW office in the afternoon, where I met Guyo, Communications Officer for East Africa, for a discussion on logistics and footage we were hoping to get - as much as that’s possible given the wildlife involved and the unpredictability of the African bush!

To get you into the mood for this rather long blog, here’s a 2 minute video of some of the highlights that are about to follow…

After a 5am start the next morning, I was on the way to Wilson Airstrip for a short flight eastward, heading to the airstrip of Amboseli National Park at the foot of Tanzania’s Kilimanjaro mountain – the iconic backdrop of the park, and also my next destination, as I planned to climb it in early June.

Old Friends

After landing, my first happy “sighting” was Dickson, one of the best wildlife guides I’ve ever worked with, and who had gladly agreed to help me again during this visit – his network of contacts across rangers, local Maasai, and other guides was invaluable for what we wanted to do. In addition, he had also been working for months to secure us an off-road permit in the park, greatly increasing the chances for unique sightings and photographic angles.

To complete the paperwork for that, we stopped at the Kenya Wildlife Service headquarters and then straight away made our way out into the plains, bushes, marshes, and lakes of Amboseli and its surrounding areas. While we were able to plan when to visit the ranger bases, it’s more difficult to make plans with the wildlife (insert corny joke about sending a meeting invite to Craig). Nevertheless, I had high hopes that during the 5 days I would be able to spend here, at least a glimpse of Craig would be achievable. During my previous visit, it took 3 days of searching and coordinating until we finally got a message that he had been seen in a conservancy outside the park. While elephant herds often follow a routine, lone large older bulls are not as predictable: they can roam over thousands of square kilometres, not stopped by park boundaries or even national borders.

A Reunion with Craig

Let me cut this short – my worry about whether I’d be able to find Craig again this time was luckily unfounded. In fact, I could not believe what occurred – just a few hours after landing on the airstrip, I stood in front of him again, gently walking towards the marsh, watching him enter the water for a drink and some fresh grass.

While his figure is in fact not among the largest elephants in the park, it’s his tusks and the gentle, yet imposing presence that truly makes you feel in awe when watching this magnificent animal. At 53, Craig is no longer a youngster, has seen and done it all, and is not fazed by human presence. His age also means that there is not much time left for him: aside from poaching, disease, or other unnatural deaths, elephant lifespan is primarily dictated by their molars. With six sets lasting 10 years each, it’s usually in their 60s when they’re unable to chew anymore and face starvation. As we left him alone for the morning and made our way to the lodge, I felt a sense of relief and gratitude that I already had been able to document him again so early in my trip. Even before my first trip to Amboseli, I enjoyed seeing elephants in the wild, but observing them up close here has given me a new level of appreciation for their complex social structures, intelligent behaviour, and sheer size, but also the threats and difficulties they face.

Day 1 was not over yet. In the afternoon, Amboseli had another beautiful sighting in store for us: a cheetah. But she was not alone. This cheetah gave birth to a total of five cubs several months earlier, all of which she has kept alive until today, despite the threat of lions and hyena. Can you spot them all?

Although they are slowly approaching full adult size, they still rely on the mother for food and hunting guidance.

We watched them cross the plains and take a short break on a fallen tree, scanning the environment for what might be their next meal, before they disappeared into the thickets. The ecosystem here supports a healthy and stable cheetah population, although the species as a whole has been under pressure from human impact on its range, and is considered the most vulnerable of the big cats. There are less than 7000 cheetah left in the world, spread over only 10% of their former range.

We happen to come across them another time on our second day, giving me a few more opportunities to capture their elegant lean shapes in the tall grass as they stalked a herd of gazelle.

This year luckily brought the significant water needed to sustain the ecosystem. In the past, droughts have been quite severe, resulting in the deaths of many elephants and other species from competition for water. Even today, water access is a challenge as human needs conflict with the requirements of the wildlife – an elephant needs to drink up to 200 litres per day, for instance!

Clouds and a bit of drizzle also accompanied this afternoon, but it made my second encounter with Craig even more special. We spotted him in the distance not far from where he had been roaming around in the morning, when I saw a faint rainbow in the eastern clouds. Dickson and I rushed to him with the hope we’d be able to get a special photo. We only had a few minutes, and at first Craig didn’t cooperate, showing us his backside… but our patience was rewarded when he turned to the side, and I could snap a few images with him and the last glow of the rainbow. You never know what nature has in store!

The last light faded, rains appeared on the horizon, and we made our way back to the lodge.

Team Lioness

For Day 2, we planned an early morning start, heading to the north of the National Park into the surrounding community lands. The goal was one of IFAW’s most well-known ranger bases: the home of Team Lioness, an all-female ranger team, which began its duty in 2019 and now consists of 17 members in total. Its story is a special one for several reasons: the members are often the first women in their families to secure employment, and at the same time break the mould of a traditionally male-dominated domain, taking on the role of protector against poaching and mitigator of human-wildlife conflict.

On Patrol

One of their ranges gave me a short briefing on the day’s activities: typically, they wake up at 6:30, followed by exercise and morning tea, and then a patrol, during which the team reports back findings to the headquarters. They normally walk for 20 km per day, but were happy to cut their route a bit shorter that day – lucky me, it was hot.

The first interesting observation? Two male rangers stayed behind, taking care of one of the Team Lioness member’s young child – unexpected gender role reversal indeed. Evelyn tells me it’s great for her to be able to go to work while knowing that her young one is safe at the base.

As we explore the area, Leah shares that they look for tracks to identify animal activity, with the goal of determine the number of animals moving in the conservancy, and any sick animals or other unusual signs. I watched them map wildlife sightings, and communicating findings using GPS coordinates over the radio to the central base of the area. We spotted zebra, gerenuk, giraffe, and other wildlife from a distance – it’s not common to run into the more dangerous animals such as buffalo or lion during the day, but Team Lioness is not allowed to carry weapons with them (only the Kenya Wildlife Service has the permission to do so), so you always need to be on high alert. Nevertheless, walking through the bush on foot is a very different and much more intimate experience than in a Safari vehicle, and brings you much closer to nature.

I had the chance to spend a little bit of time with them after the patrol, and they revealed some of their motivations for becoming a ranger, hurdles they faced in their communities, and goals for the future. Leah says she wants to pass the knowledge she gained working for IFAW to her kids so that they would also be interested in preserving wildlife for future generations. Human-wildlife conflict is one of the biggest challenges she sees in this goal, as it is a constant struggle to prevent and mitigate the consequences of lions seeing herds of goat or cows as prey for instance, while keeping the communities positive about wildlife, which is critical to its protection. I didn’t know it yet, but we would see an example of this issue first-hand a few days later. I asked her what her favorite animal is - which was probably not a very creative question –and unsurprisingly, the answer was Lioness, because “she’s a hardworking woman”.

One of their newest members, Doreen, is just 24 and joined the team in January. Over a cup of tea, she tells me the reason she joined was to protect the wildlife and culture of her homeland, and it was something that she already cared about back in school. After some jobs in retail and hotels, she found out about the chance to join Team Lioness. She didn’t face a lot of reluctance from the men around her, but they told her the work would be hard. She laughed as she tells me that actually, she finds it “quite easy and enjoyable”.

Although it’s difficult to connect with people in just a few hours, and admittedly many members of Team Lioness are quite reserved (who can blame them, they became rangers to protect wildlife, not to be interviewed by me), I was still happy and grateful they let me into their routine. We shared a few moments of laughter, and I gained some insights into their motivations and goals, and a better understanding what it means to be a female IFAW ranger on a day to day basis.

Here is a short video IFAW and I created with a few more clips of my visit to Team Lioness - inspiring!

The Allure of the Tuskers

Aside from my time with Team Lioness, the day brought with it two more big “Tusker” sightings: elephants of the name of Per, and Wickstrom (they are named by the Amboseli Elephant Trust, but don’t ask me how they come up with these names…).

For Per, it was a beautiful morning sighting on our way to Team Lioness, watching him slowly wake up and start his day. Once you spend more time with these elephants, it’s also easy to see how different they look: Per has a more sturdy, wider figure and head than Craig for example, and his eyes are set deep with large black borders, giving him a mix of scary and sad appearance at the same time.

In the afternoon, the clouds lifted for the first time, revealing Amboseli’s famous backdrop – Kilimanjaro, Africa’s tallest mountain. While it’s situated within Tanzania’s borders, it’s undeniably (for me anyway, having stood on both sides and a few days later, also on the summit) Kenya that got the better view of the iconic flat top with its (ever shrinking) glaciers. As the mountain appeared in the background, our goal became to combine Amboseli’s incredible elephants with what is probably Africa’s most typical fauna, the Tortilis Acacia, and the iconic landscape – a postcard photo.

Just as the day ended after a couple of hours looking for this exact scenery, things came together when I spotted a big elephant in the distance, slowly approaching a beautiful acacia tree to scratch his skin. We rushed through the bumpy thickets, positioned ourselves, and managed to take some images. Wickstrom has beautiful symmetric tusks, and at age 42, he’s in his prime. A true privilege to see him under these conditions.

Day 3 - Above the Clouds

The next day started very, very, early, but for good reason – it was time to see this ecosystem from a different perspective. The plan to do that? A balloon flight. Leaving the lodge around 4am, I headed to the boundary of the park, with the hope to explore the landscape from above. The evening before was cloudy and windy, so this hope was slightly diminished given that the weather conditions around Kilimanjaro are often unpredictable.

And indeed, as we left, not a single star was visible, making it clear to me that a thick cloud layer put the chances for a beautiful sunrise and a great view of the mountain into question. However, my experience with cloud conditions and flights (balloon, helicopter, drone, or otherwise) told me that sometimes a less promising outlook holds opportunities for something special. It would turn out that I wasn’t wrong, but as we watched the balloon inflate and then climbed into the basket around 6am, the thick cloud cover I had suspected was confirmed as daylight crept in.

We gently rose into the air and came closer and closer to the white ceiling above us – until we were fully engulfed by what seemed like white, cool, humid smoke. Seeing absolutely nothing when looking around was of course not why you’d fly in a balloon, but the temporary blindness only lasted a few seconds.

At this point, we breached the cloud layer at an altitude of around 6000 feet, and it was like entering another world: the magical sunrise on one side, and a clear view of Kilimanjaro above the clouds on the other, with the snow-capped peak illuminated by early rays emanating from our home star. I have been lucky to experience many beautiful things in life, but can’t deny that this brought a smile on my face.

It was another sign that sometimes it’s ok to let nature do its thing and embrace what you get, rather than trying to force it, a lesson I also try to apply to wildlife encounters (but sometimes struggle with in other parts of life 😃).

Our pilot (and my hunch about the local weather conditions) told me that it’s not uncommon to be able to have this experience, but it’s by no means a given: there are plenty of clear days (which are beautiful of course, but a little less interesting) and also days with heavier cloud cover or stronger winds that don’t allow the balloon to simply pop up above the cloud layer. As we dropped below the white blanket again the sun also made an appearance over the landscape for a few moments, and we descended over the Maasai bomas (villages), their cattle, kids going to school, and a few animals as well: hyena, giraffe, wildebeest, zebra, gazelle, and ostrich could be spotted from the air.

After another half an hour of quietly (this is one of the things that makes balloon flights special) hovering over Amboseli, it was time to land before we got close to the nearby mountain ridges. A small bump into the tree canopy and a few bumps over some bushes, and we were back on the ground.

After a short drive back and the obligatory balloon champagne celebration (non-alcoholic for me), we encountered a beautiful large herd of elephant crossing the road towards the marsh from the forest area, and I spotted a female with very large tusks, as well as some juveniles engaging in playful behaviour. Making a mental note to ask Dickson about the female later, it was time to head back to camp.

For the afternoon, we had a decision to make: Craig was spotted on the other side of the park in the morning, but so were some lions. It’s hard for me to say no cats of any kind, but as there were glimpses of Kilimanjaro between the clouds and one of the photos I was still looking for was the iconic view of Craig and the mountain, there was only one right choice to make: you can never go wrong with spending time with this creature, it’s almost therapeutic to watch him go about his business. Although that business didn’t quite include plans to face the right way for the Kilimanjaro photo, we got quite close to what I was looking for, with two egrets adding to the show. These birds follow elephants in the hope that their movement stirs up insects on the ground, which they can then feast on (one reason elephants are sometimes called the ecosystem engineers).

Real Human-Wildlife Conflict

We planned our second ranger base visit for the morning of Day 4, heading to the north of the park into the Illaingarunyoni Conservancy, where IFAW opened a new base in 2023.

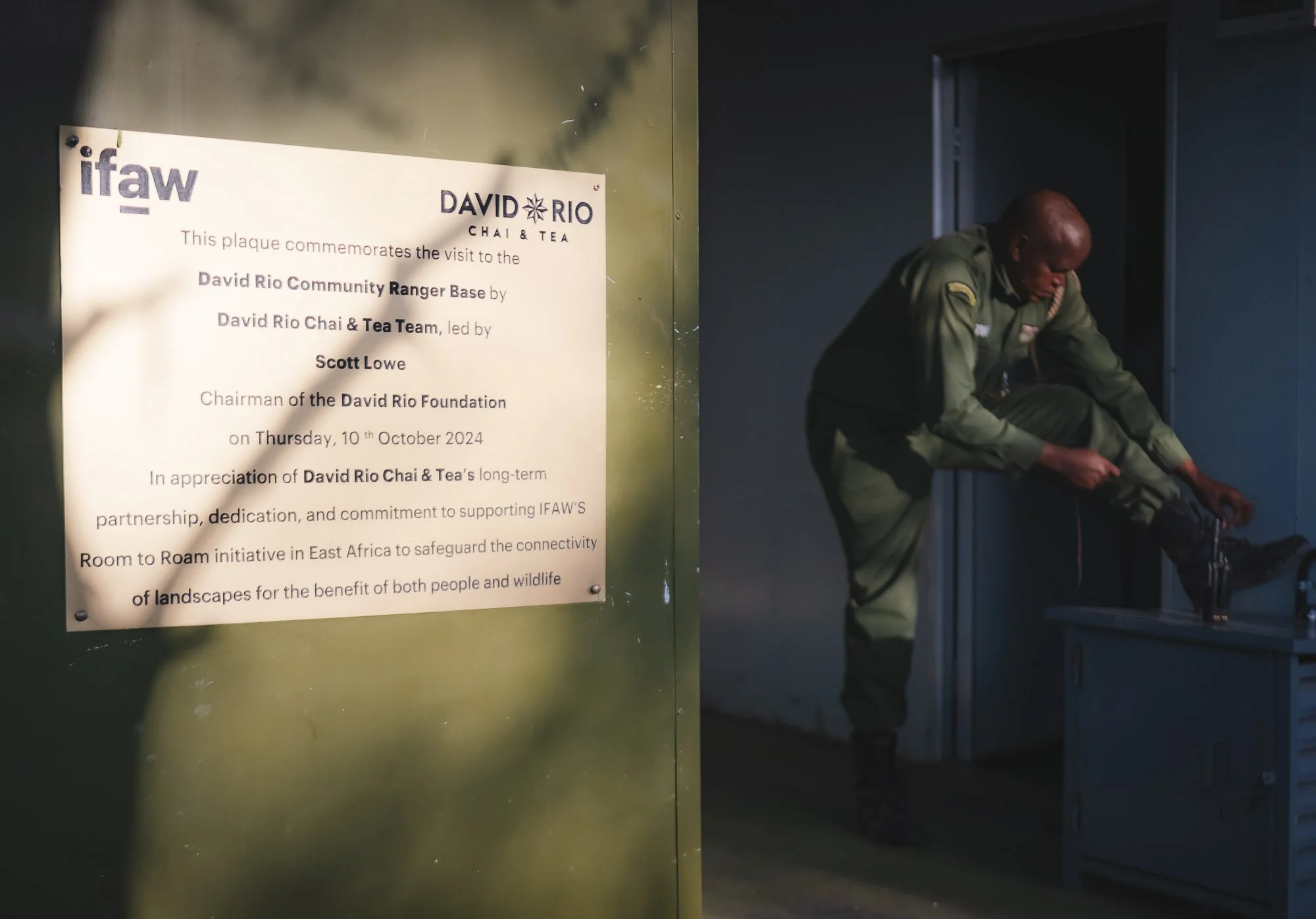

This base is named after and was established in partnership with David Rio, a chai tea company from the US – a rather unusual collaboration, but their foundation has been active in the area for many years. These partnerships are invaluable for IFAW’s work here, which is not only limited to set up a ranger base and help manage human-wildlife conflict. Leasing land and working with government, researchers, and local communities as well as the landowners (in this case through a formal agreement with the Olgulului-Ololorashi Group Ranch) to establish animal corridors and ensure there is sufficient space for wildlife to move around is another key activity.

One such project is IFAW’s “Room to Roam”, a visionary approach to conservation established across different parts of Africa with the goal of secure elephant migration paths and habitats, while considering the needs of the local community, sharing land and resources. This is not an easy task, and we got to experience why first hand during my visit.

But one thing at a time. We arrived at the base in the early morning, and had the chance to see the team of rangers get ready – only men this time. Moses, the head of the group here, gave me a quick introduction, and then checked in with the rangers in the area if there was any news – funnily enough, we heard the voices of Team Lioness on the radio!

Indeed, for today there was a rather unusual incident that required their attention: a male elephant had been raiding the crops of a nearby Maasai village over the last days, culminating in a major incident the evening before our visit: the elephant turned over a car. The ranger team was planning to visit the incident to understand what happened, and how to deal with the problem, but they did not have a car available to themselves – a major constraint in their day to day job.

Dickson and I had a solution: we offered to take them in our Land Cruiser, and they happily agreed, so after some morning tea and a briefing, we all headed out together. While on the one hand this was possibly a serious incident, it would maybe give me the chance to observe a real life example of human-wildlife conflict.

On the way I had a chance to ask Moses a few questions about his life as a ranger and why he chose to get into this profession. He started 10 years ago, primarily with the goal of support his family and four kids. But he quickly learned that there is more to the job than just subsistence, and it became a mission for him to protect the wildlife. In his words:

“when the animals disappear, our children will not see how we see”.

But it’s been challenging, as they often lack the resources to intervene effectively. Our case was a prime example, as he tells me they would have been able to move to the incident much earlier if they had a dedicated car. According to him, this kind of human-wildlife conflict is one of the primary challenges they face: for a lion, killing a cow is survival for a few days, but that cow is also the source of income guaranteeing food on the table for a local family, or education for their kids – it was a familiar topic to me by now.

As we arrived at the Maasai boma, the rangers first checked in with the village head if I was allowed to enter and take photos – not a given in the protective Maasai community. Luckily, they had no objections, and we joined the discussion of the group and learned a few more details: the head of the conservancy had sent his three sons in an (IFAW-sponsored) vehicle to the affected boma.

They attempted to scare off the elephant with the car, and chase him out of the area. The bull however had none of it, attacked the car a few hundred metres from the field, and turned it over, injuring the occupants, who fled the scene. Luckily the injuries were relatively minor - especially given the state of the car on the photo I was able to see, this could have been much worse.

They showed the rangers and myself the crops that the elephant had raided. It was a very large area, around 1 acre, almost completely trampled and emptied of whatever vegetables and fruits were growing there, mostly tomato. That’s a major problem for the local community, and they were visibly upset.

We then wanted to head out to the scene of the car being turned over, but around half way were stopped as the Kenya Wildlife Service approached. IFAW’s rangers facilitate, monitor, and support, but the KWS is the only organisation allowed to carry guns, and make decisions about wildlife. As their vehicle arrived, more people showed up, and a larger discussion ensued. My understanding was that the Maasai were advocating for the elephant to be killed, while others proposed he'd be chased away and moved from the area.

What happened?

These decisions are not clear cut. An elephant who encroaches on settlements regularly and acts aggressively is a real threat, not just directly to the affected local community, but by extension also through the risk that his behaviour might spread to other elephant herds, creating a larger issue. From what we understood, this bull was migrating from the Tsavo ecosystem, where many elephants are less calm and not as relaxed around humans as here in Amboseli, where conflict is less common. In addition, inaction on the KWS’ part might trigger self-justice by the Maasai, who are fierce warriors: killing an elephant with spears is not beyond their realm of ability, at great risk to themselves and with a painful death for the animal.

Even more so, it would foster a general animosity to wildlife and a distrust towards the organisations protecting it, as they might be seen to disregard community needs, making future collaboration much more difficult. Within these discussions, it became clear to me that my presence, especially with a camera, was not completely without controversy – the typical fate of a documentary photographer and (so I’d imagine) even more so of a journalist. Simply being there as an outsider could alter the behaviour of the people.

This might not be for nefarious reasons - one can imagine a wide range of motivations: the Maasai may not want to be negatively portrayed as advocating to kill animals in western press, or the KWS may think that without outsiders, stakeholders would act more rationally and not try to prove anything. I can only speculate what ultimately triggered the decision to ask us to leave.

Either way, not wanting to aggravate the situation, Dickson and I sadly made our way back before seeing the vehicle or understand the next steps. But not before sharing our thanks to the David Rio Ranger team, and of course exchanging the obligatory selfie and contact details. At this point, we didn’t know what the outcome of the situation would be, but had hopes we might find out later.

As we left, I realised once more the complexities of the overall system that organisations like IFAW need to work in, and the many decisions and opinions that cannot be simply reduced to black and white, even though that is sometimes the way it is superficially portrayed in news on social media, for instance.

A Final Moment with Craig

Back in Amboseli, the afternoon gave me a fourth and final encounter with Craig as he made his way to the northern end of the park, most likely crossing into a conservancy where he’d be much more difficult to find over the next days. Once again, we had plenty of time alone with him while he was feeding and slowly moving from bush to bush, giving me the chance to observe him from the ground, kneeling in front of the car as he calmly walked by. Having experienced what it’s like to be completely exposed as a three-and-a-half metre, five-tonne elephant with two-metre long tusks passes you so close that you could touch him, I’ll always see these creatures in a different light.

There is no way to develop the same respect for their presence from the elevated safety of a vehicle, or in front of a fenced zoo enclosure. There are very few places in the world where it is imaginable to be so close to a wild elephant without danger, or without triggering their curiosity and thus altering their behaviour – something an ethical observer should avoid whenever possible. Craig’s calm demeanor around vehicles and people is what makes this experience feasible, but a wild animal will always remain a wild animal, and should be respected accordingly – there is no guaranteed safety, as we had seen first-hand at the ranger base in the morning. In the same vein, I have unfortunately also experienced how some guides would push their cars into Craig’s path at the last second to get the best close up view, and it makes me increasingly angry to witness this – it’s almost a personal affront, a cringeworthy feeling that makes you want to apologise to this majestic animal for being part of the human species. How much of this must he have endured over his 53 year lifespan, and yet he’s still accepting our presence?

It was these mixed emotions, and the lasting impression of the morning, that we let Craig disappear into the distance, hoping he’d stay out of trouble. In fact, one worry that is always present here is that males like him would cross into Tanzania, where they are less protected, and human wildlife conflict and especially trophy hunting in the Enduimet Area of Tanzania has cost many elephant lives, including several large tuskers in 2023 and 2024.

The Amboseli Elephant Trust has been advocating to end this with some success for more than 30 years, but it seems policies have changed over the last years and the moratorium on hunting in the area was lifted. This is a major issue for the elephant population, as bulls enter their most active reproductive years in their 40s – an age many of them don’t reach.

Let’s hope Craig won't be next.

We spent the last hour of the day reflecting on this, soaking up Kilimanjaro views with wildebeest and waterbucks as the sun set behind us.

Day 5

Although I said goodbye to Craig for this trip, that didn’t mean that my time looking for elephants was over. Remember the female with the large tusks? I wanted to try and see her again, so we headed out early in the morning towards the east, where she’d typically cross from the forest into the marshes, often accompanied by a few large family groups. Just after the sun rose, we did indeed spot her where expected – elephant families have very specific routines they generally follow. It was a clear day, and that meant it was time for more images with the beautiful Kilimanjaro backdrop.

Hollie

Hollie is actually rather small in terms of body size, even for a female, but her tusks are seriously impressive and beautifully symmetric. More often than not, one tusk is used significantly more than the other (depending on whether the elephant is right- or left-tusked, if you will) and that also means they don’t always face exactly the same way.

She also has very large ears, shaped like the map of Africa, and with a distinct cut on the left one. Aside from the wide ears, her body also seemed wider than normal, which could indicate a pregnancy – wouldn’t it be amazing if her and Craig could produce a few more Super Tuskers… let’s hope for the best.

We had a few more beautiful observations of her family group passing through the savannah on their way to the marshes, and also ran into one of the most famous elephant researchers in the world, Cynthia Moss, who was observing them and making notes of their movements. She has been studying the elephants of Amboseli for five decades, and is the founder of the Amboseli Elephant Research Project and its associated Trust. Her books “Portraits in the Wild” and “Elephant Memories: Thirteen Years in the Life of an Elephant Family” are certainly going to be one of my next reads.

The afternoon was spent slowly, exploring more of the fauna and flora of the region. Amboseli is home to 400 species of birds, 80 types of mammals, and 300 plant species, aside from its gorgeous landscape.

The morning of Day 6 marked my last few hours in the park, with an early drive towards the border crossing with Tanzania. I was going to climb Kilimanjaro, after looking at it many times over the last days, mostly with mixed feelings of awe, respect, and excitement.

The Tarakea border is just over an hour from the gates of Amboseli National Park towards the Tsavo region, Kenya’s largest protected area. Of course, nature had one more beautiful morning elephant sighting for us in store before we made our way to the KWS Headquarters again to finish the paperwork required to leave.

I received this photo of the car the elephant had turned over. They’re strong animals…

This is also where I learned of the fate of the elephant that had been raiding the crops in the conservancy where the David Rio ranger base is located: the KWS ranger transparently told us that the decision was made to eliminate him. While this is a sad outcome of the story in one way, for the reasons I mentioned earlier, it may ultimately be the most beneficial long-term option for the ecosystem as a whole, and the growing number of elephants and continued thriving biodiversity in the area with limited conflict serves as evidence to confirm this hunch.

Yet, it’s a stark reminder of the difficulty conservation organisations face, and at the same time clearly shows their importance. Ultimately, it made me appreciate the time I spent in Amboseli and the opportunity to document it with such deep access to its inner workings even more. But now it was time for the next adventure, I had a mountain to climb – and can imagine that this is also a good metaphor for how the task to protect our wild world must feel for organisations like IFAW.